Week 3

Race, Ethnicity, and Nation

Soci—269

Racial Classification, Nationhood, Politics–

September 17th

Some Housekeeping

Response Memos

Response Memo Deadline

Your second response memo—which has to be between 250-400 words and posted on our Moodle Discussion Board—is due by 8:00 PM tonight.

Some Housekeeping

Next Week’s Class Structure

Next week, we’re going to adjust ever-so-slightly modify our schedule.

We will finish our conversation about Race, Ethnicity, and Nation on Monday, before discussing Class and Social Stratification on Wednesday.

Some Housekeeping

Next Week’s Class Structure

Therefore, next week’s response memos are also due on

Wednesday at 8:00 PM.

Let’s Talk Boundaries

What Are “Boundaries?”

In recent years, the idea of “boundaries” has come to play a key role in important new lines of scholarship across the social sciences. It has been associated with research on cognition, social and collective identity, commensuration, census categories, cultural capital, cultural membership, racial and ethnic group positioning, hegemonic masculinity, professional jurisdictions, scientific controversies, group rights, immigration, and contentious politics, to mention only some of the most visible examples.

(Lamont and Molnár 2002:167, EMPHASIS ADDED)

What Are “Boundaries?”

Great! But what are boundaries?

What Are “Boundaries?”

Any takes?

What Are “Boundaries?”

Symbolic Boundaries

Symbolic boundaries are conceptual distinctions made by social actors to categorize objects, people, practices, and even time and space. They are tools by which individuals and groups struggle over and come to agree upon definitions of reality. Examining them allows us to capture the dynamic dimensions of social relations, as groups compete in the production, diffusion, and institutionalization of alternative systems and principles of classifications. Symbolic boundaries also separate people into groups and generate feelings of similarity and group membership … They are an essential medium through which people acquire status and monopolize resources.

(Lamont and Molnár 2002:168, EMPHASIS ADDED)

What Are “Boundaries?”

Social Boundaries

Social boundaries are objectified forms of social differences manifested in unequal access to and unequal distribution of resources (material and nonmaterial) and social opportunities. They are also revealed in stable behavioral patterns of association, as manifested in connubiality and commensality. Only when symbolic boundaries are widely agreed upon can they take on a constraining character and pattern social interaction in important ways. Moreover, only then can they become social boundaries, i.e., translate, for instance, into identifiable patterns of social exclusion or class and racial segregation.

(Lamont and Molnár 2002:168–69, EMPHASIS ADDED)

What Are “Boundaries?”

[S]ymbolic and social boundaries should be viewed as equally real: The former exist at the intersubjective level whereas the latter manifest themselves as groupings of individuals. At the causal level, symbolic boundaries can be thought of as a necessary but insufficient condition for the existence of social boundaries.

(Lamont and Molnár 2002:169, EMPHASIS ADDED)

What Are “Boundaries?”

Consider the process of collective identification.

What Are “Boundaries?”

Although collective identity formation is commonly conceptualized as a self-referential process, it usually also involves self-conscious efforts by members of a group to distinguish themselves from whom they are not, and hence it is better understood as a dialectical process whose key feature is the delineation of boundaries between “us” and “not us.”

(Zolberg and Woon 1999:8, EMPHASIS ADDED)

What Are “Boundaries?”

An Example

For a relevant paper, see Kuran (1998).

Boundary-Making

Boundaries in Flux

Crucially, boundaries are mutable and dynamic. Moreover, the distribution of people on either side of a boundary is

not time-invariant or set in stone

(see Abascal 2020).

Boundaries in Flux

But how do these evolutionary shifts take root?

Let’s consider Zolberg and Woon’s (1999)

influential typology.

Boundaries in Flux

There are three basic strategies that individuals and social groups can pursue to navigate—and perhaps remake—the social and symbolic boundaries that pervade greater society.

Boundary Crossing

Boundary Blurring

Boundary Shifting

Boundaries in Flux

Individual boundary crossing … (occurs) without any change in the structure of the receiving society and leaving the distinction between insiders and outsiders unaffected. This is the commonplace process whereby immigrants change themselves by acquiring some of the attributes of the host identity. Examples include replacing their mother tongue with the host language, naturalization, and religious conversion.

(Zolberg and Woon 1999:8, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Boundary blurring … (is) based on a broader definition of integration—one that affects the structure (i.e., the legal, social, and cultural boundaries) of the receiving society. Its core feature is the tolerance of multiple memberships and an overlapping of collective identities hitherto thought to be separate and mutually exclusive; it is the taming or domestication of what was once seen as “alien” differences. Examples include formal or informal public bilingualism, the possibility of dual nationality, and the institutionalization of immigrant faiths (including public recognition, where relevant).

(Zolberg and Woon 1999:8–9, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Boundary shifting … denotes a reconstruction of a group’s identity, whereby the line differentiating members from nonmembers is relocated, either in the direction of inclusion or exclusion. This is a more comprehensive process, which brings about a more fundamental redefinition of the situation. By and large, the rhetoric of pro-immigration activists and of immigrants themselves can be read as arguments on behalf of the expansion of boundaries to encompass newcomers, while that of the anti-immigrant groups can be read as an attempt to redefine them restrictively in order to exclude them.

(Zolberg and Woon 1999:9, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Boundary Crossing

Boundary Blurring

Boundary Shifting: Contraction

Boundary Shifting: Expansion

Sidebar:

A Crude Introduction to Causal Inference I

Does X Cause Y?

Social scientists are often interested in drawing causal inferences.

X \to Y

About what, exactly? There are a dizzying array of examples. Here are three questions that (implicity or explicitly) invite causal claims:

Do smaller class sizes improve pedagogical outcomes?

Will investments in family planning programs improve economic and health outcomes for women in low-income settings?

Did the cultural grievances of the “middle class” trigger the rise of fascist politics in interwar Europe?

Does X Cause Y?

We can, of course, deploy quantitative tools (e.g., estimators, weighting, causal diagrams, experiments) to “resolve” these questions—or at least adduce evidence grounded in statistical reasoning.

Does X Cause Y?

For simplicity, let’s assume that our (three) outcomes of substantive interest are approximately linear. Can we estimate a linear regression model to “resolve” our three research questions?

y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x + \epsilon

The Answer

It depends.Correlation \neq Causation

Some Examples

Correlation \neq Causation

Some Examples

Correlation \neq Causation

Some Examples

Correlation \neq Causation

Some Examples

Correlation \neq Causation

Some Examples

Correlation \neq Causation

How can experiments provide a path forward?

Contraction & Group Threat

(Abascal 2020)

Latino Ambiguity

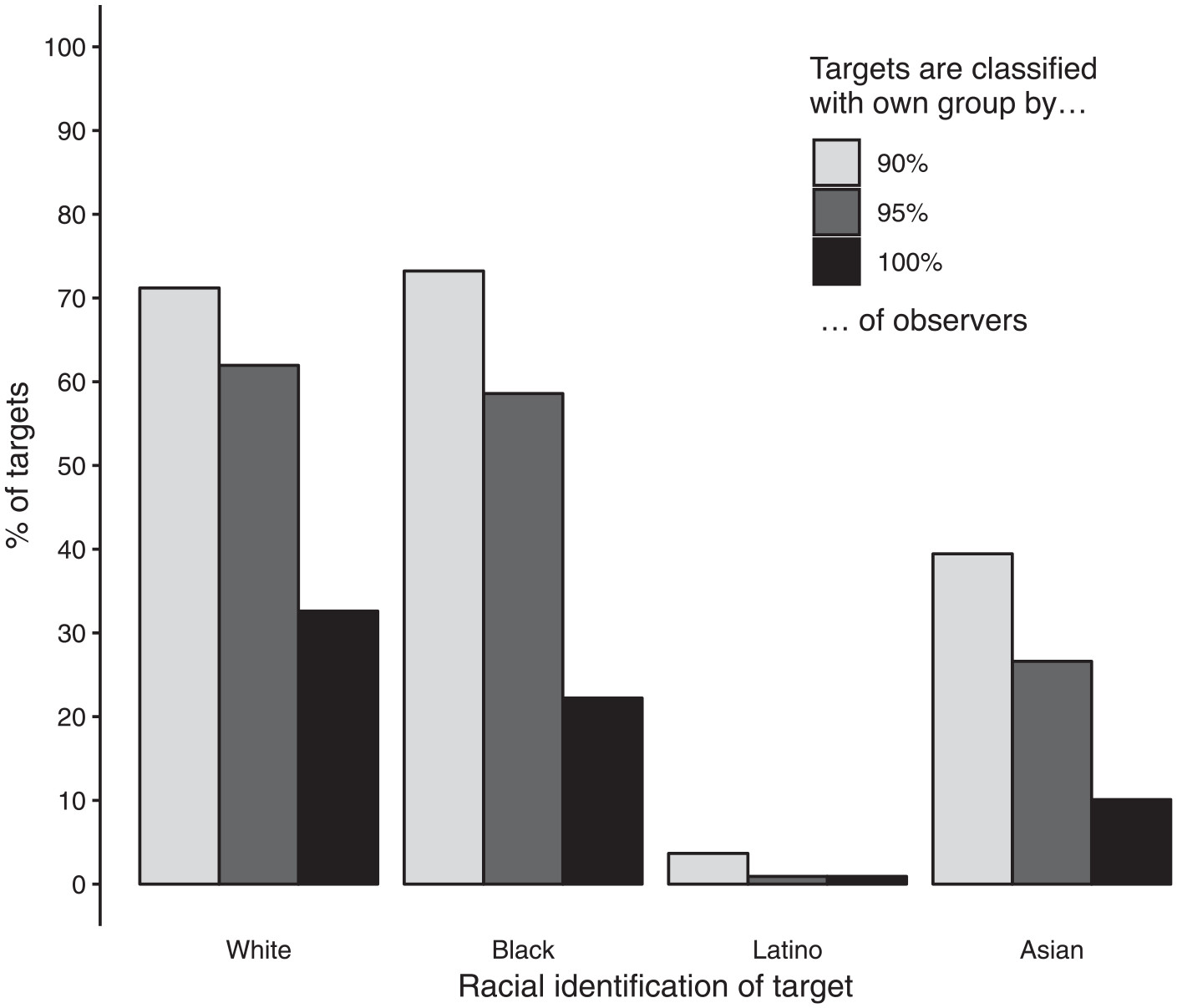

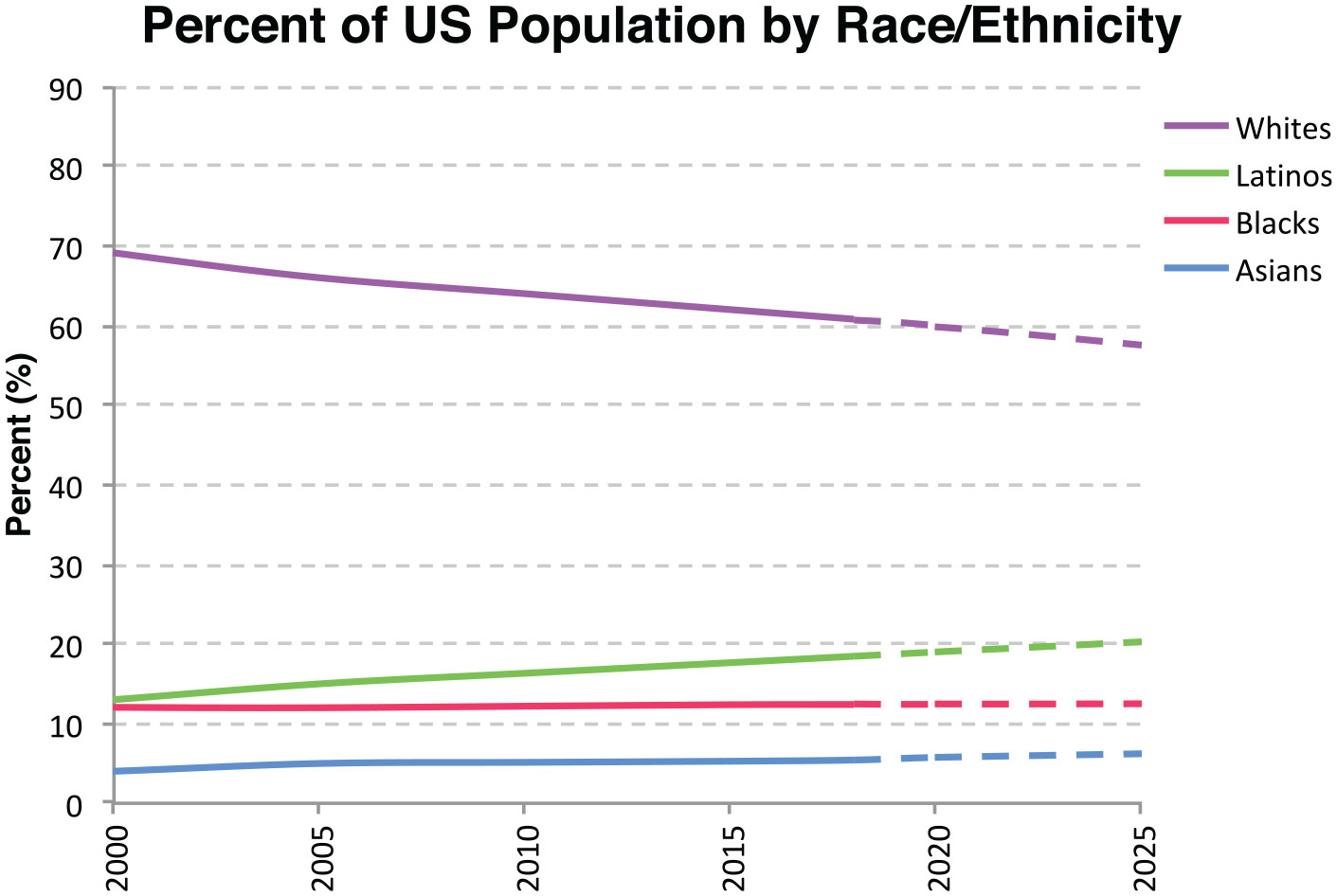

[S]elf-identified Latinos, who are themselves heterogeneous in terms of ancestry and phenotype, are probably the primary source of racial ambiguity in the United States today. A look at a racially diverse face database makes the point. The Chicago Face Database (CFD) … is a publicly available database of nearly 600 people who self-identify as White, Black, Latino, or Asian …[C]oncordance between self- and other-classification is lowest for self-identified Latinos. Concordance is highest for self-identified Whites and self-identified Blacks.

(Abascal 2020:304, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Latino Ambiguity

Figure 1 from Abascal (2020).

Latino Ambiguity

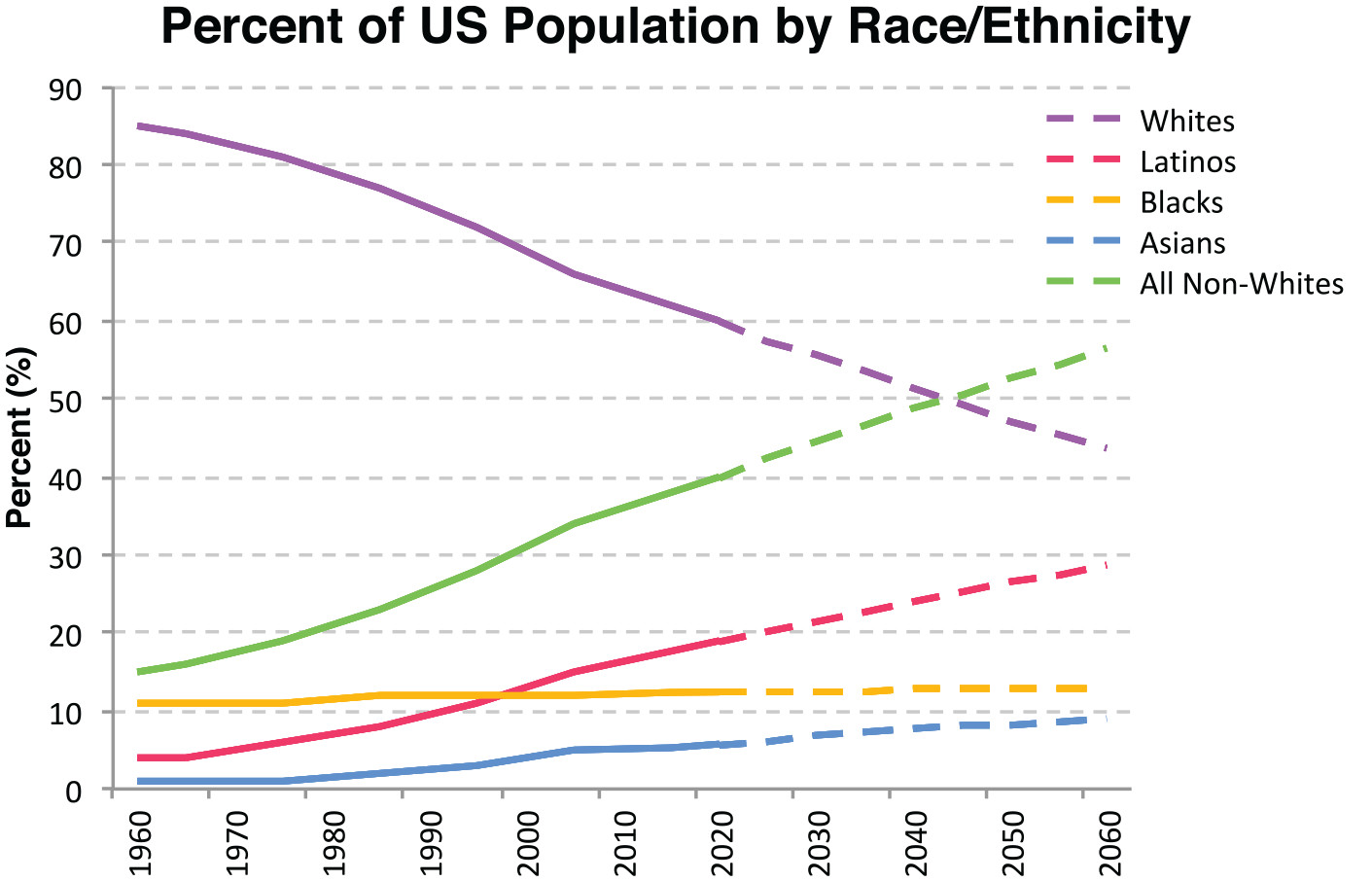

As a result, Latino Americans will play a key role in the evolution

of ethnoracial boundaries in the United States.

Latino Ambiguity

White people who are prompted to think about the changing demographics of the United States are less likely to classify people who are ambiguously White or Latino as “White.” This suggests White people respond to demographic threat by contracting the boundary around Whiteness.

(Abascal 2020:302, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Latino Ambiguity

What does this mean, exactly?

Latino Ambiguity

Studies consistently find that White people are more likely to marry and live near Latinos than Blacks … [T]hese facts are taken to mean that “racial boundaries are more prominent, and the black/white divide more salient than the Asian/white or Latino/white divides” (Lee and Bean 2004:229). However, social scientists have also observed that both intermarriage and integration are lower in areas where immigration is higher … Explanations for this association typically stress structural features of communities rather than individual preferences … (My) findings suggest preferences may also play a role: White people in high-immigration areas might be less likely to count Latinos as candidates for inclusion in White social spaces. In short, where Latinos are more concentrated, the White/Latino boundary is brighter and the benchmark for being considered “honorary Whites” higher.

(Abascal 2020:316, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Latino Ambiguity

More fundamentally, (my) findings imply that White people will increasingly fortify the boundary separating Whites from non-Whites as the Latino and Asian populations continue to grow and the U.S. population diversifies.

(Abascal 2020:316, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Exercise I

Abascal’s Experimental Framework

Some Context

Abascal’s Experimental Framework

Some Questions

Group 1

How does Abascal (2020) use Figures A1 and A2 (see the appendix) to adjudicate her guiding assumptions?

Group 2

How does Abascal (2020) use the “faces” in Section E of her Supplemental File to conduct her survey experiment?

Quantifying Nationalism

Scholarly Conceptions of Nationalism

| Political (focus on elites’ political projects and discursive practices) |

Quotidian (focus on lived culture, ideas, and sentiments of non-elites) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Ideology (“nationalism” refers to narrow set of ideas) |

Gellner (1983:1): “a political principle, which holds that the political and the national unit should be congruent” | Kosterman & Feshbach (1989:271): “a perception of national superiority and an orientation toward national dominance” |

| Practice (“nationalism” refers to a domain of meaningful social practice) |

Brubaker (2004:116): “a claim on people’s loyalty, on their attention, on their solidarity [. . .] used [. . .] to change the way people see themselves, to mobilize loyalties, kindle energies, and articulate demands” | Brubaker (1996:10): “a heterogeneous set of ‘nation’-oriented idioms, practices, and possibilities that are continuously available or ‘endemic’ in modern cultural and political life” |

Nationalism as Political Project

.jpg)

John Gast’s American Progress

Nationalism as Political Project

Combat et prise de la Crête-à-Pierrot by Auguste Raffet

(engraving by Ernst Hébert)

Quotidian Forms of Nationalism

Quotidian Forms of Nationalism

Popular Nationalism

The Nationalism of Individuals

As Ideology

Nationalist ideology … is not solely the domain of political elites seeking to legitimize their rule over a territorially bounded people. For political psychologists, nationalism is a set of dispositions that cohere at the level of individual actors.

(Bonikowski 2016:429, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Nationalism of Individuals

As Ideology

Political psychologists tend to view nationalism (i.e., chauvinism) as a normative problem … but [p]otentially invidious dispositions toward the nation … are not limited to chauvinism; they also include exclusionary conceptions of national membership, excessive forms of national pride, and strong identification with the nation above all other communities. Furthermore, the standard distinction in this literature between nationalism and its ostensibly benign counterpart, patriotism, is fraught with analytical difficulty.

(Bonikowski 2016:430, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Nationalism of Individuals

As Practice

Nationalism is not only a conscious ideology, it is also a discursive and cognitive frame through which people understand the world, navigate social interactions, engage in coordinated action, and make political claims.

(Bonikowski 2016:430, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Nationalism of Individuals

As Practice

If the operative mode of nationalism-as-ideology is to effect political change in the interest of national sovereignty, nationalism-as-practice involves people thinking, talking, and acting through and with the nation.

(Bonikowski 2016:430, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Nationalism of Individuals

As Practice

Research on nationalism in everyday life … examines how the nation is understood and deployed in routine interactions (Brubaker 1996). This may manifest itself through explicit references to the nation, but just as often,nationalism’s influence is more tacit, expressed in habituated modes of thought, speech, and behavior that take for granted the nation’s cultural and political primacy.

(Bonikowski 2016:431, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Nationalism of Individuals

Bonikowski’s (2016) Primary Goal

To integrate “sociological research on nationalism as a meaningful category of practice and political psychology scholarship on nationalist attitudes.”

(cf. Bonikowski 2016:431)

Schemas of the Nation

A Site of Symbolic Struggle

The nation is not a static cultural object with a single shared meaning, but a site of active political contestation between cultural communities with strikingly different belief systems. Such conflicts are at the heart of contemporary political debates in the United States and Europe.

(Bonikowski 2016:428, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Disparate Understandings of the Nation

[I]f we are to understand how people perceive the nation, we ought to capture the wide range of beliefs and symbolic representations that constitute people’s nation schemas. These are likely to include tropes about the nation’s character, salient national symbols and traditions, perceptions of the nation’s appropriate symbolic boundaries, feelings of pride in the nation’s heritage and its institutions, and views about the nation’s relationship to the rest of the world.

(Bonikowski 2016:437, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Disparate Understandings of the Nation

More simply, popular nationalism taps into the following questions:

Who Is a Legitimate Member of the Nation?

What Are the Nation’s Virtues?

What Is the Nation’s Place in the World?

Crucially, different “thought communities” nested in the general population will have substantively different answers to these questions.

Disparate Understandings of the Nation

Disparate Understandings of the Nation

Disparate Understandings of the Nation

Disparate Understandings of the Nation

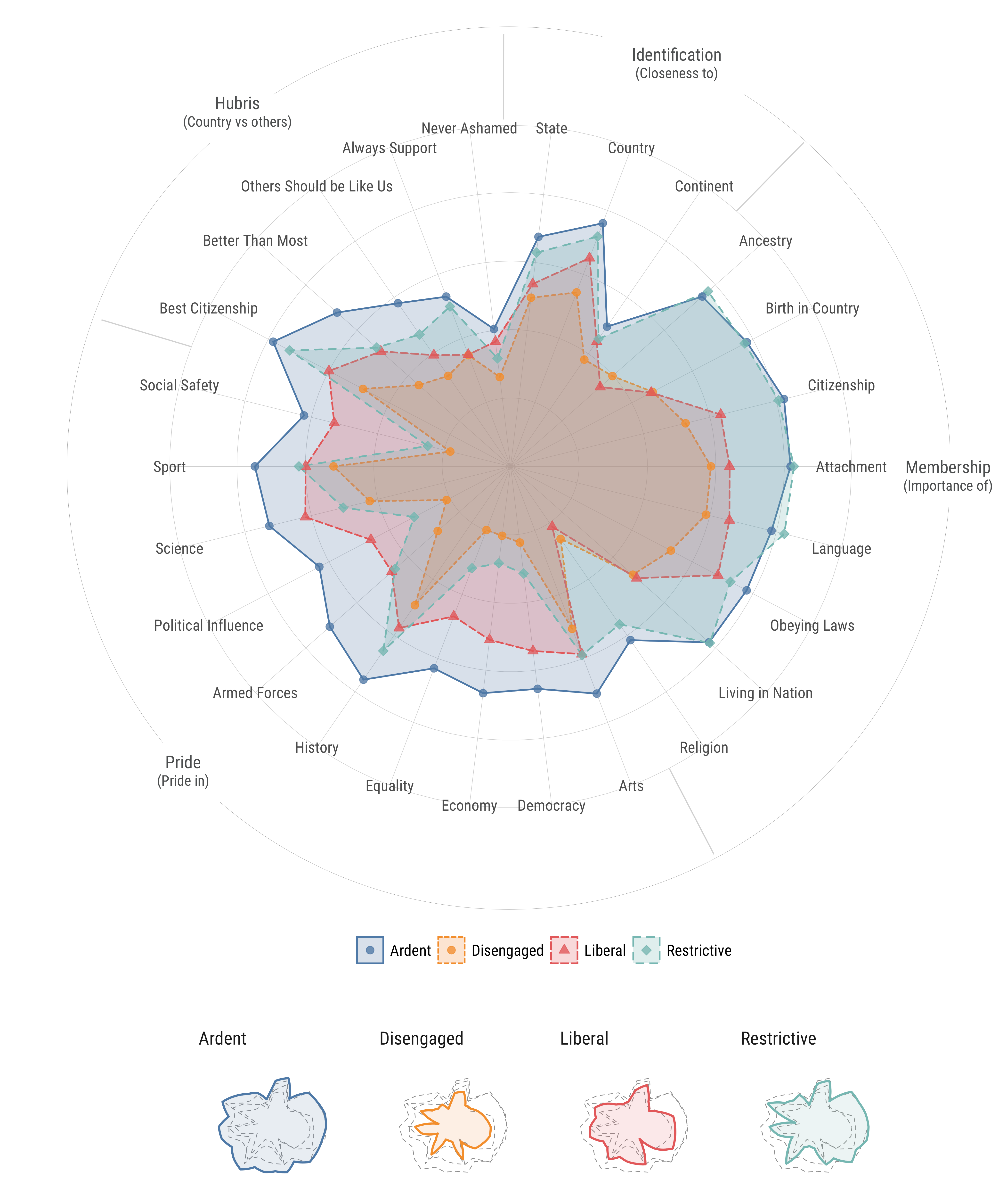

Group Exercise II

Measuring Popular Nationalism

In groups of 2-3, discuss how Bonikowski, Feinstein and Bock (2021) capture disparate understandings of nationhood using survey data.

Measuring Popular Nationalism

Figure 1 from Soehl and Karim (2021). Click to expand image.

Measuring Popular Nationalism

| Schema | Profile | Identification | Membership Criteria (Exclusionism) | Pride | Hubris |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ardent | High | High | High | High | |

| Disengaged | Low | Low | Low | Low | |

| Liberal | Moderate | Low to Moderate | High | Moderate | |

| Restrictive | Moderate | High | Low to Moderate | Moderate to High |

Race, Class, Politics–

September 22nd

Some Housekeeping

Response Memos

Response Memo Deadline

Your second response memo—which has to be between 250-400 words and posted on our Moodle Discussion Board—is due by 8:00 PM on Wedensday.

Theorizing Race, Ethnicity and Nation

A Canonical—But Contested—Perspective

We shall call “ethnic groups” those human groups that entertain a subjective belief in their common descent because of similarities of physical type or of customs or both, or because of memories of colonization and migration; this belief must be important, for the propagation of group formation; conversely, it does not matter whether or not an objective blood relationship exist. Ethnic membership (Gemeinsamkeu) differs from the kinship group precisely by being a presumed identity, not a group with concrete social action, like the latter.

(Weber 1968:389, EMPHASIS ADDED)

A Canonical—But Contested—Perspective

From this perspective, race and nationhood can be understood as subtypes of ethnicity. While race, ethnicity and nation can carry different meanings, these are often context-specific and rarely align with folk distinctions (see Brubaker, Loveman, and Stamatov 2004; Loveman 1999).

All forms of ethnicity are, in a sense, socially constructed—the product of political entrepreneurship, cultural contestation, social movements, mythcraft and the ghosts of history.

For an alternative perspective, see Winant (2015).

A Canonical—But Contested—Perspective

Even as a “construct,” the material and psychosocial consequences of ethnicity are often profound.

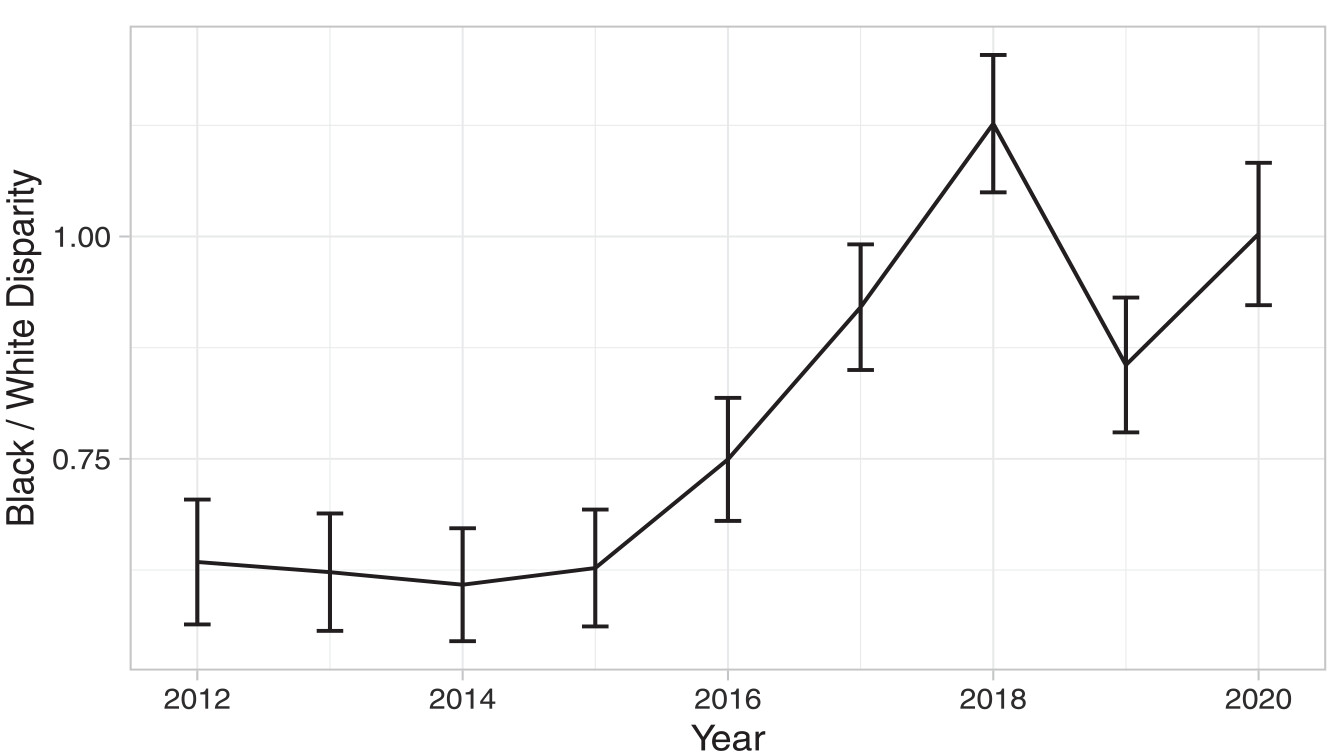

The Politics of Police

(Donahue 2023)

Partisanship, Race and Police Searches

Through an analysis of millions of highway patrol stops between 2012 and 2020, I study the treatment of Black and Hispanic motorists compared to White motorists by officers who vary in their party affiliation. I find that White officers registered with the Republican Party are significantly more likely to search Black motorists compared to White motorists than White officers registered with the Democratic Party.

(Donahue 2023:657, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Changing Politics of Police

After Trump’s election, White officers exhibited a substantial increase in their likelihood of searching Black motorists relative to White motorists … To test whether the behavior of individual officers changed, I calculate the yearly change in the Black/White disparity using an officer fixed effect … The results indicate that the same White officers became more likely to search Black motorists compared to White motorists after 2016. Next, I test whether officers hired after 2016 showed a different Black/White disparity compared to those working in 2016 or earlier … The results indicate that White officers hired after 2016 do not exhibit an additional propensity to search Black motorists when compared to White officers hired before 2016. Taken together, these results suggest the behavior of individual White officers changed throughout the study period.

(Donahue 2023:657, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Changing Politics of Police

Figure 1 from Donahue (2023).

Group Exercise III

Accounting for Other Explanations

Get up and walk around the class. Form groups of 2-3 with people you haven’t chatted with just yet. Then, discuss how Donahue (2023) tried to account for alternative explanations in his analysis.

Sidebar:

A Crude Introduction to Causal Inference II

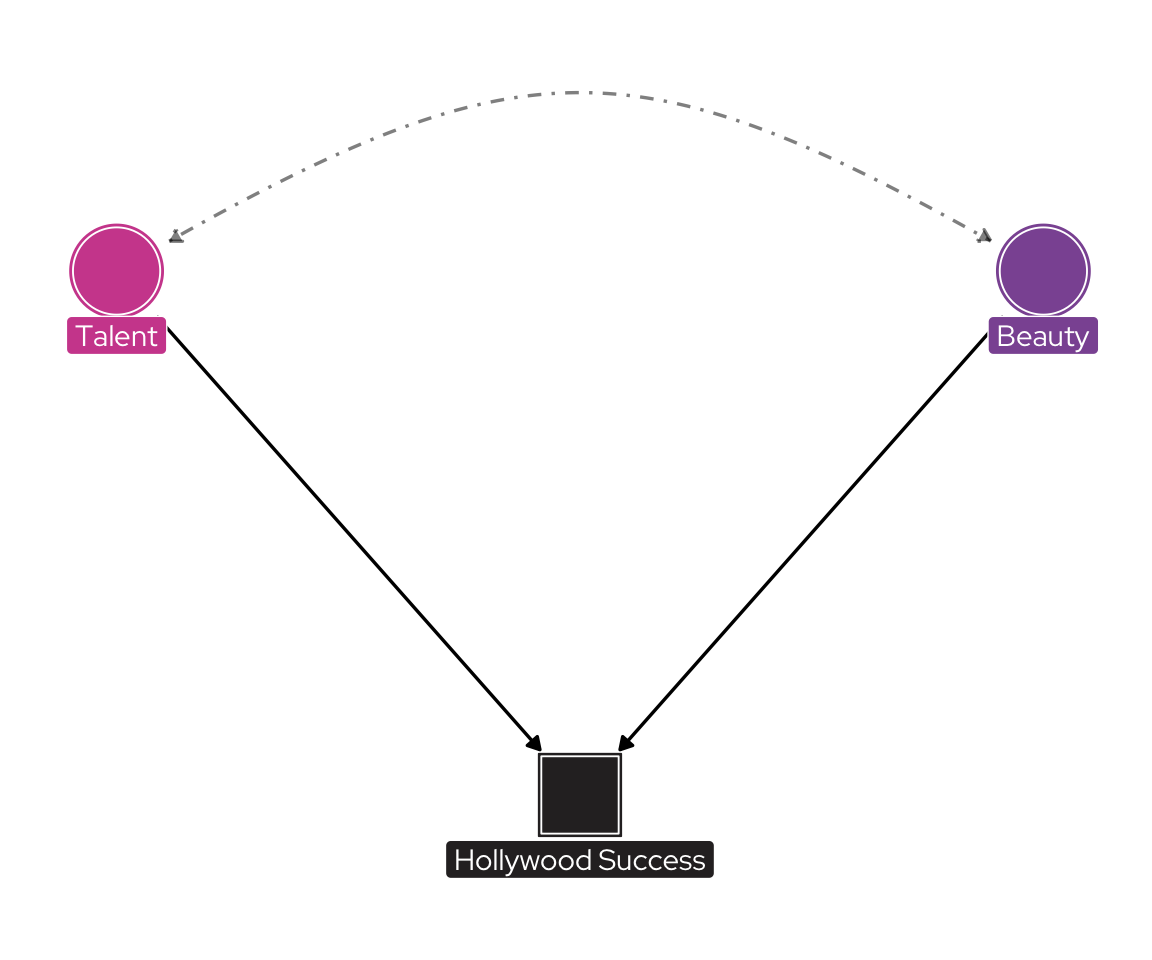

Do Not Condition on a Collider

Adaptation of Figure 4 from Elwert and Winship (2014).

Do Not Condition on a Collider

Adaptation of Figure 7 from Elwert and Winship (2014).

Do Not Condition on a Collider

Adaptation of Figure 1 from Knox, Lowe and Mummolo (2020).

Double Jeopardy

(Owens 2022)

The Entry Point

The idea that organizations, such as schools, serving predominantly Black and Latinx individuals are surveilled differently than organizations serving White people has been widely referenced in the literature … Yet, extant studies have been unable to rigorously standardize behavior and situational context across both student race/ethnicity and organizational demographic composition to rule out the possibility that differential surveillance reflects differences in student behavior across contexts. This limitation has left the scholarly and policy communities without the empirical evidence needed to understand how behavioral perceptions and responses can vary both among individuals (e.g., teachers evaluating identical misbehavior by Black or Latino versus White boys) and organizations (e.g., related to school-level student demographic composition).

(Owens 2022:1008, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Hypotheses

Figure 1 from Owens (2022).

Select Topline Findings

Adaptation of Table 3 in Owens (2022)

Note: 95% confidence intervals estimated based on table output (cf. Table 3 in Owens 2022). Ergo, they are likely a tad “off.”

Select Topline Findings

Adaptation of Table 4 in Owens (2022)

Note: 95% confidence intervals estimated based on table output (cf. Table 4 in Owens 2022). Ergo, they are likely a tad “off.”

Group Exercise IV

Blaming and Referral Climates

In new groups of 2-3, discuss how Owens (2022) tests H_3 and H_4. Does her empirical strategy differ from the strategy used to test H_1 and H_2? Ultimately, what does she find?

Group Exercise V

Race As a Resource Signal?

See You Wednesday

References

Note: Scroll to access the entire bibliography

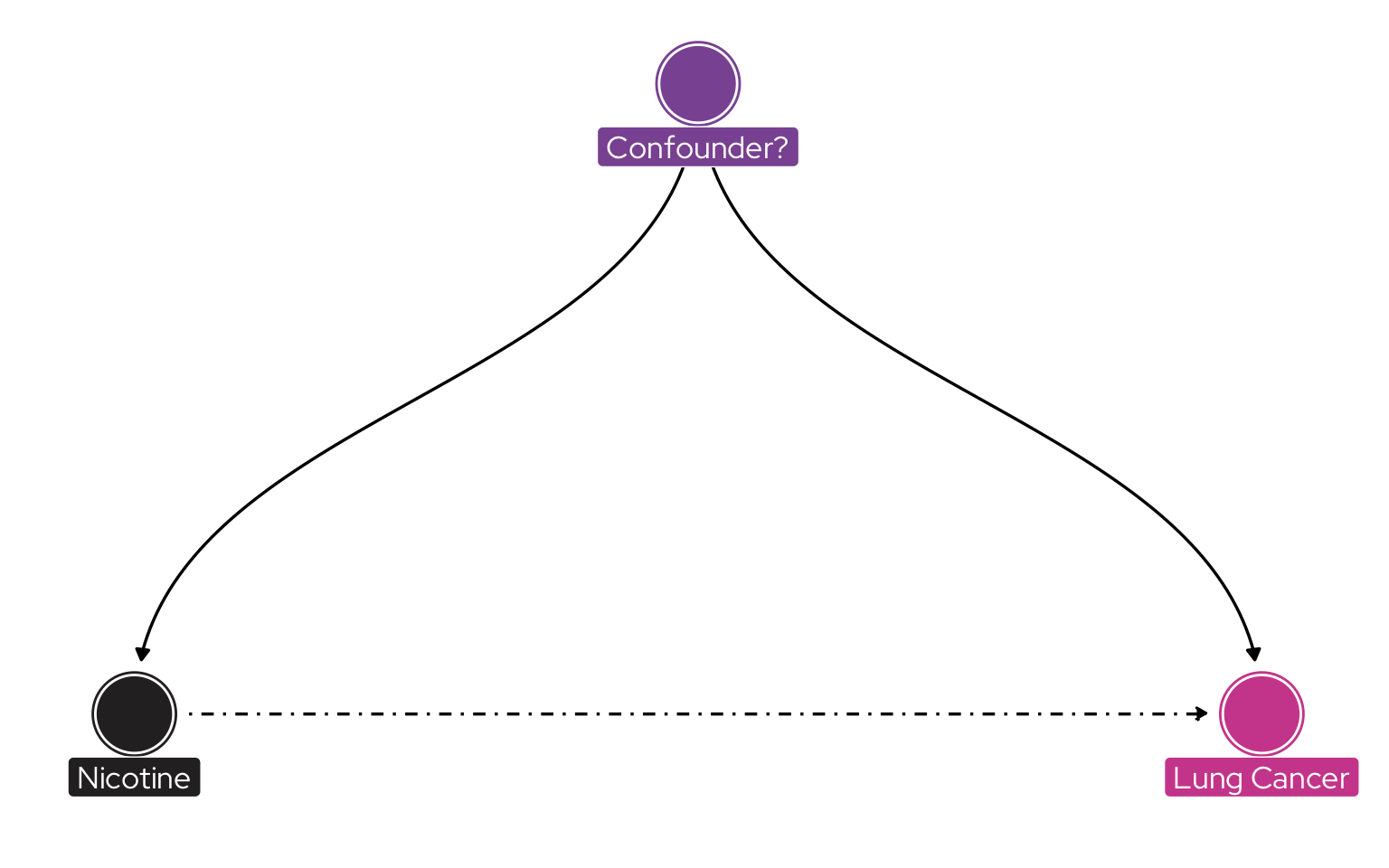

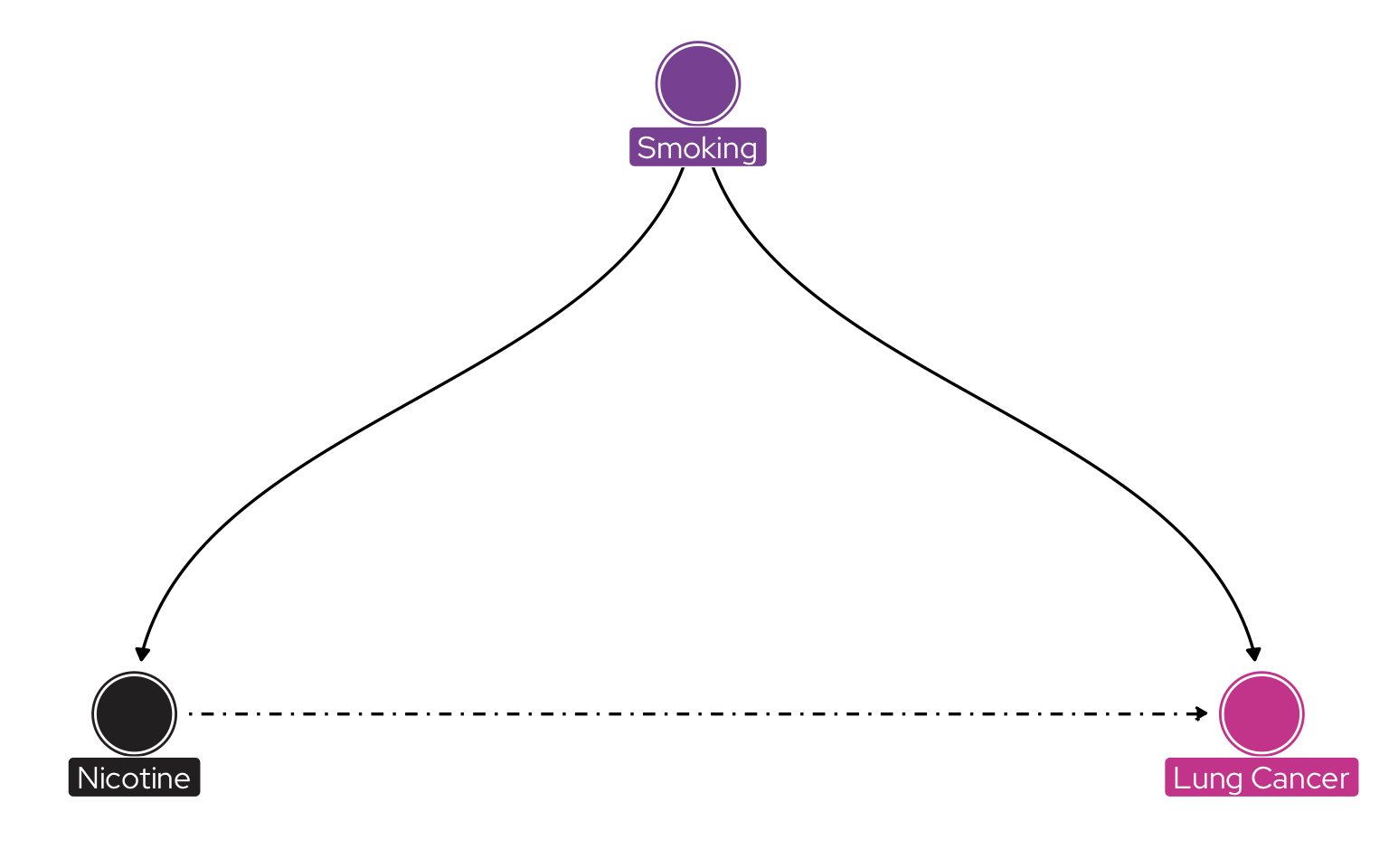

Why might nicotine consumption and lung cancer be correlated?

Smoking is the confounder in this instance.

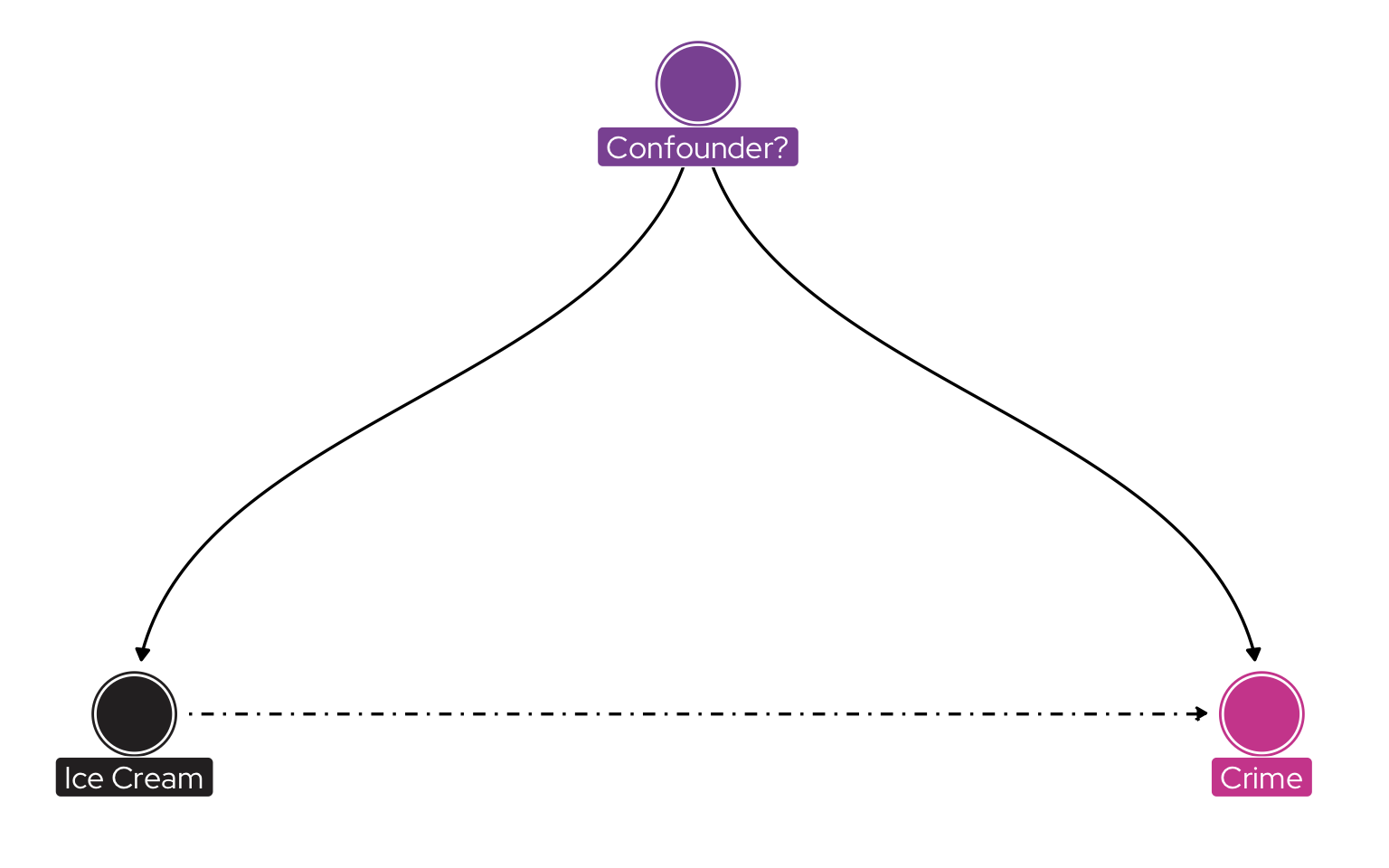

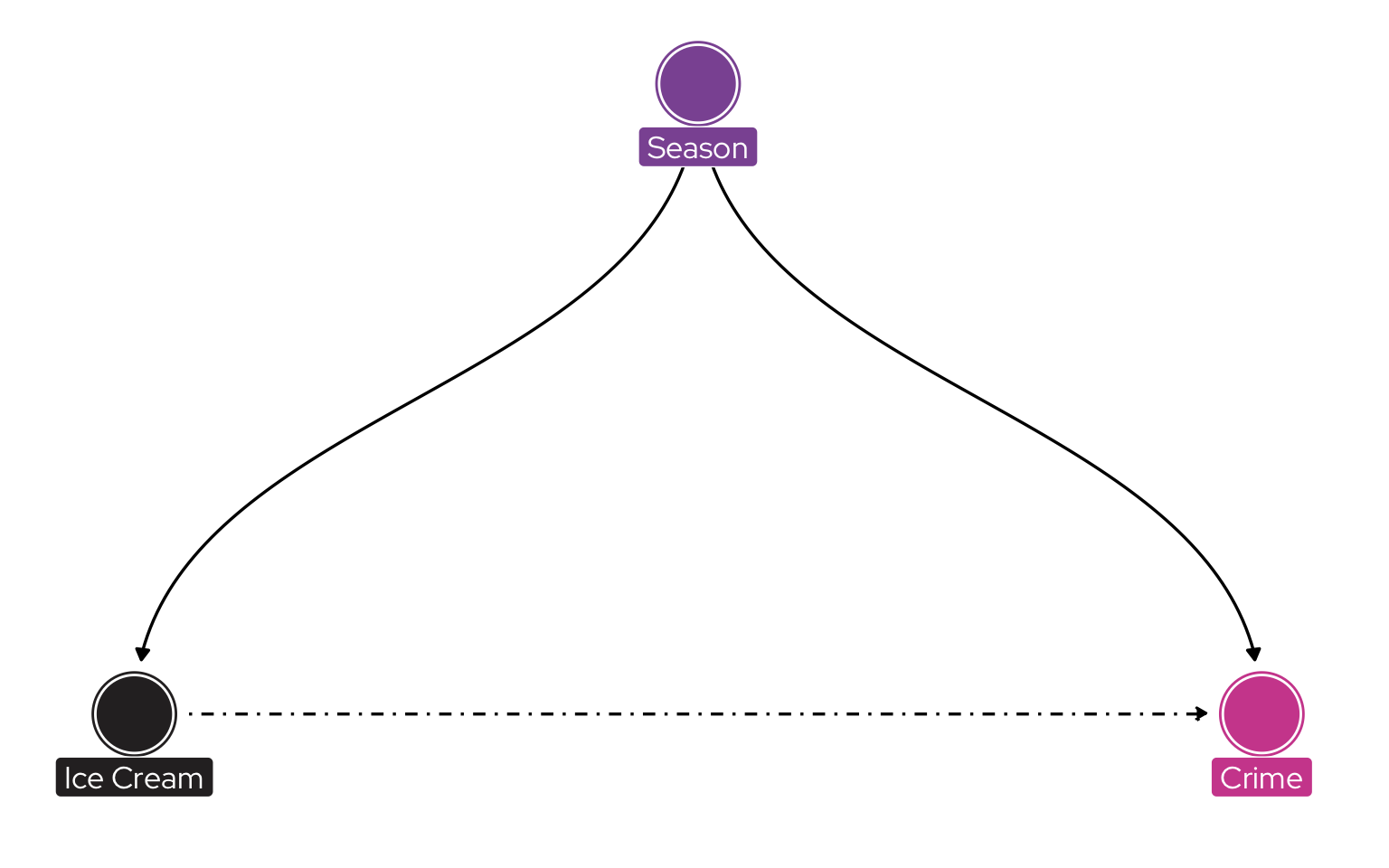

Why might ice cream sales and crime be correlated?

Season/temperature is the confounder in this instance.

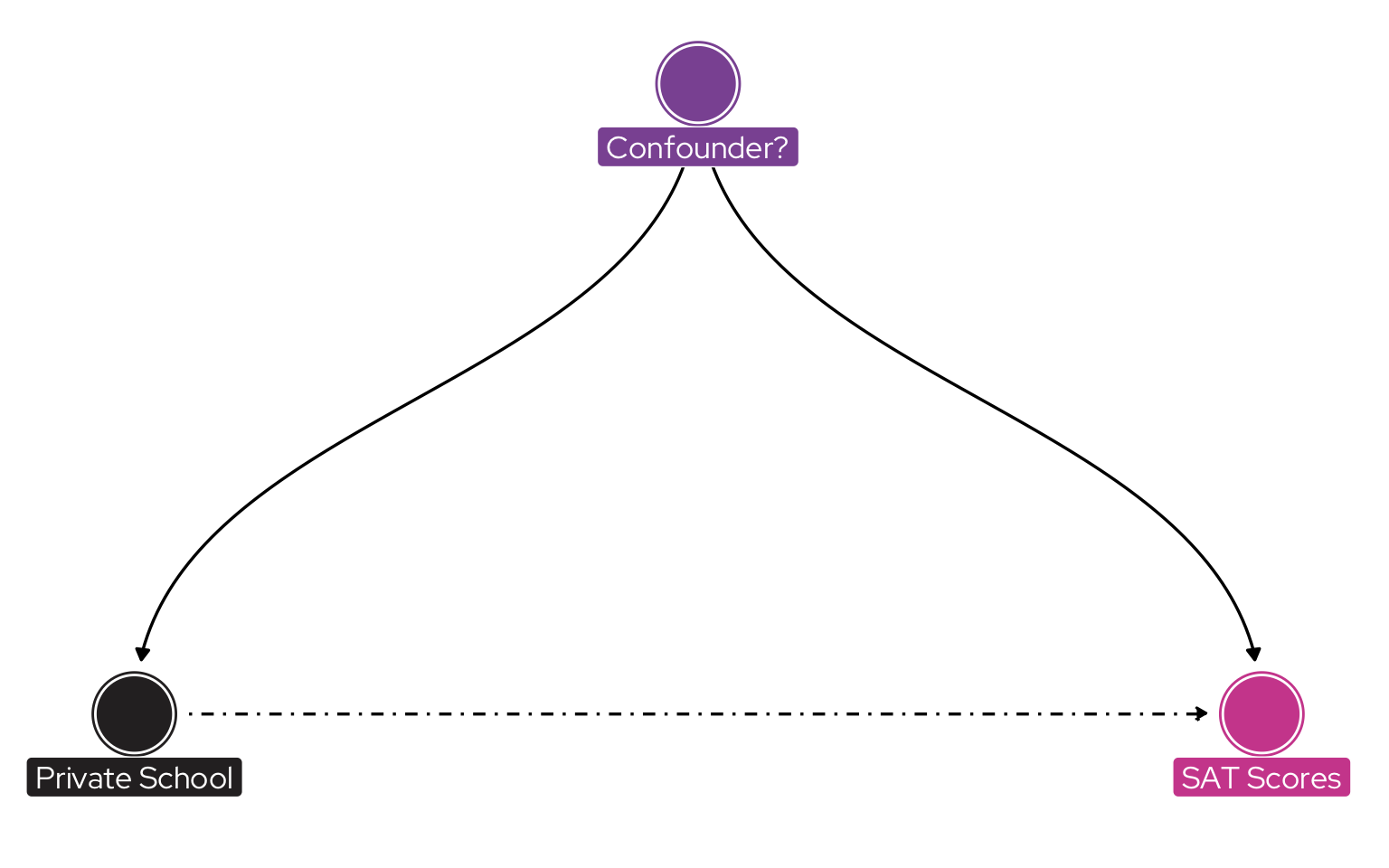

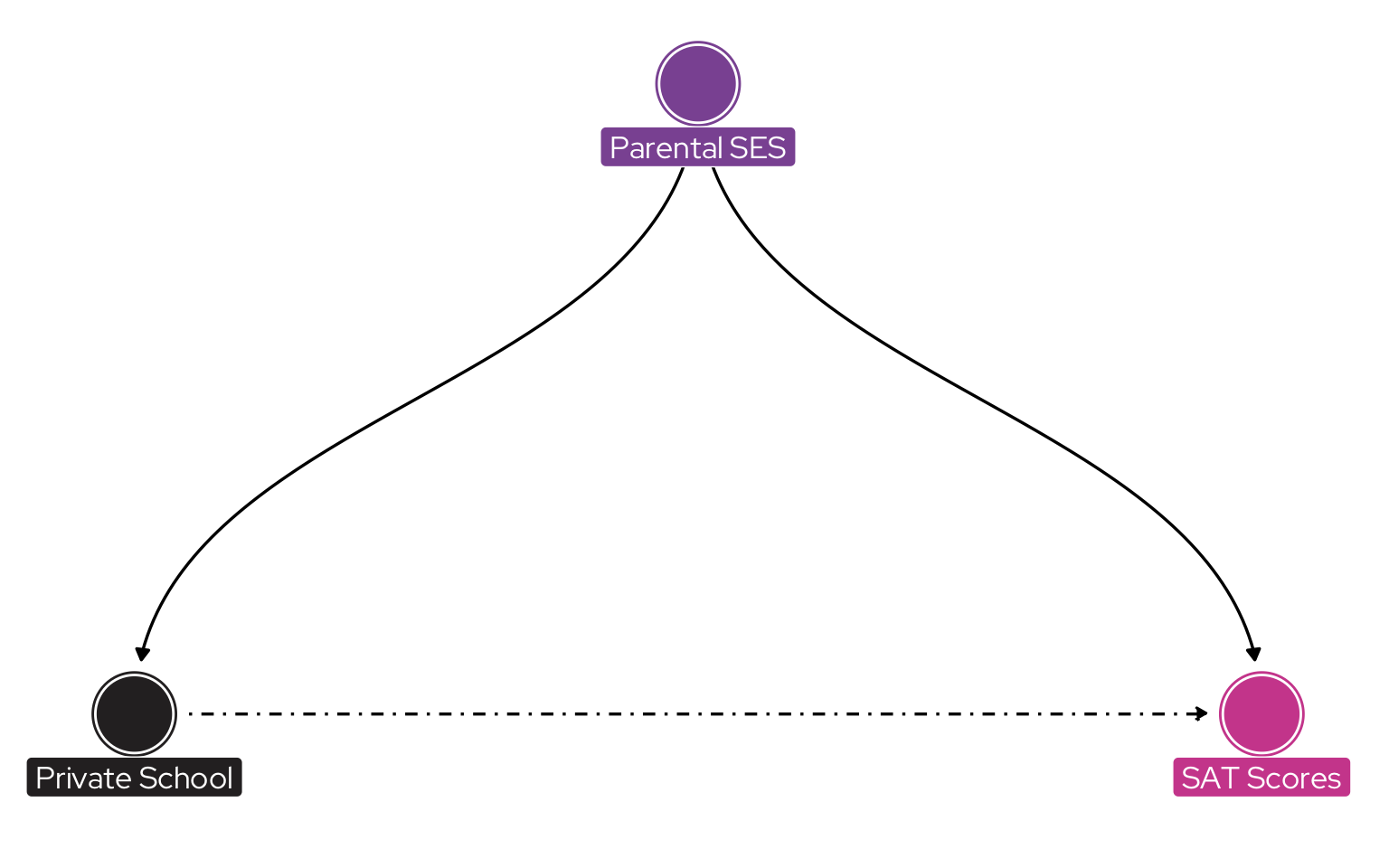

Why might private school attendance and SAT scores be correlated?

Parental socioeconomic status is the confounder in this instance.

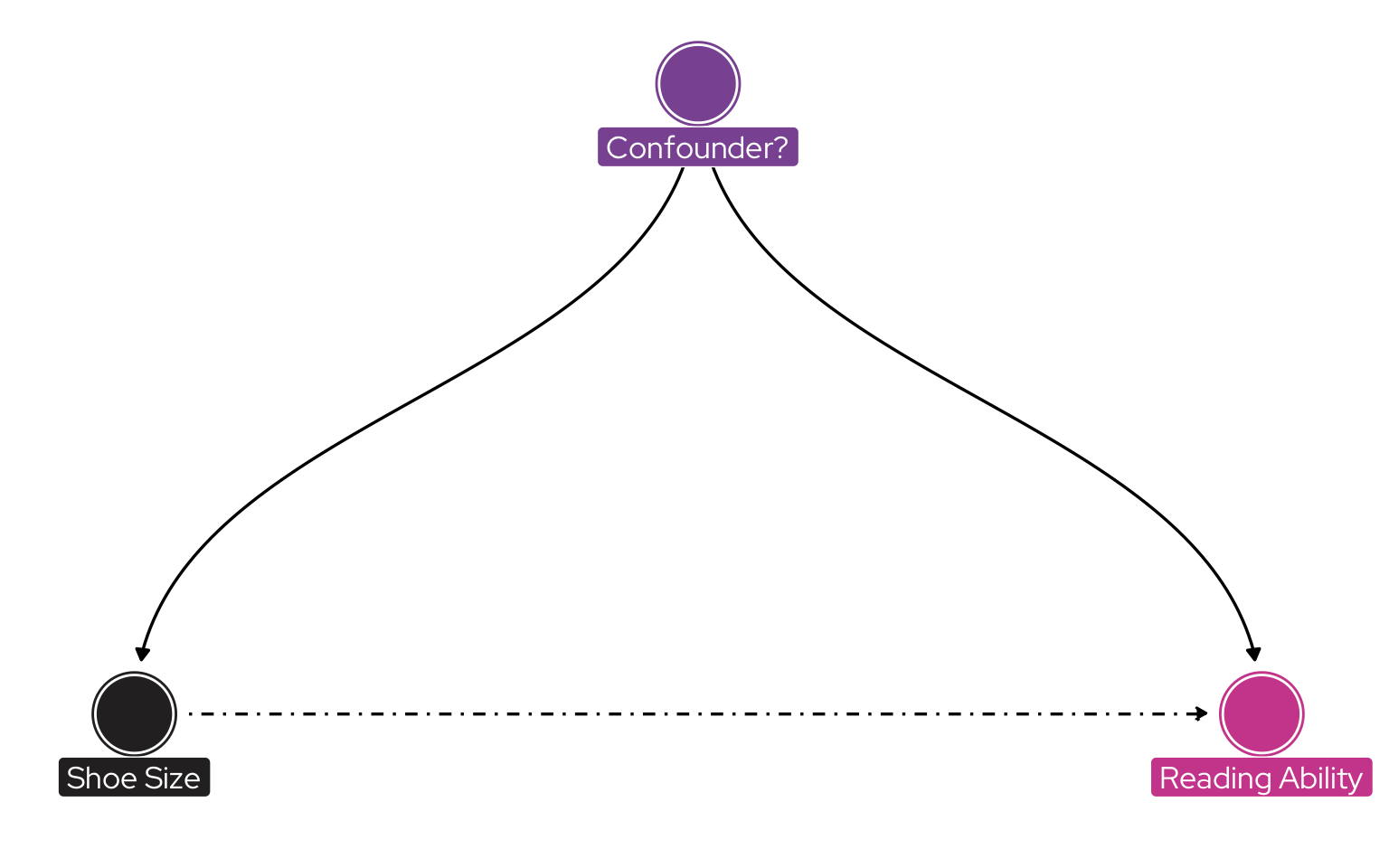

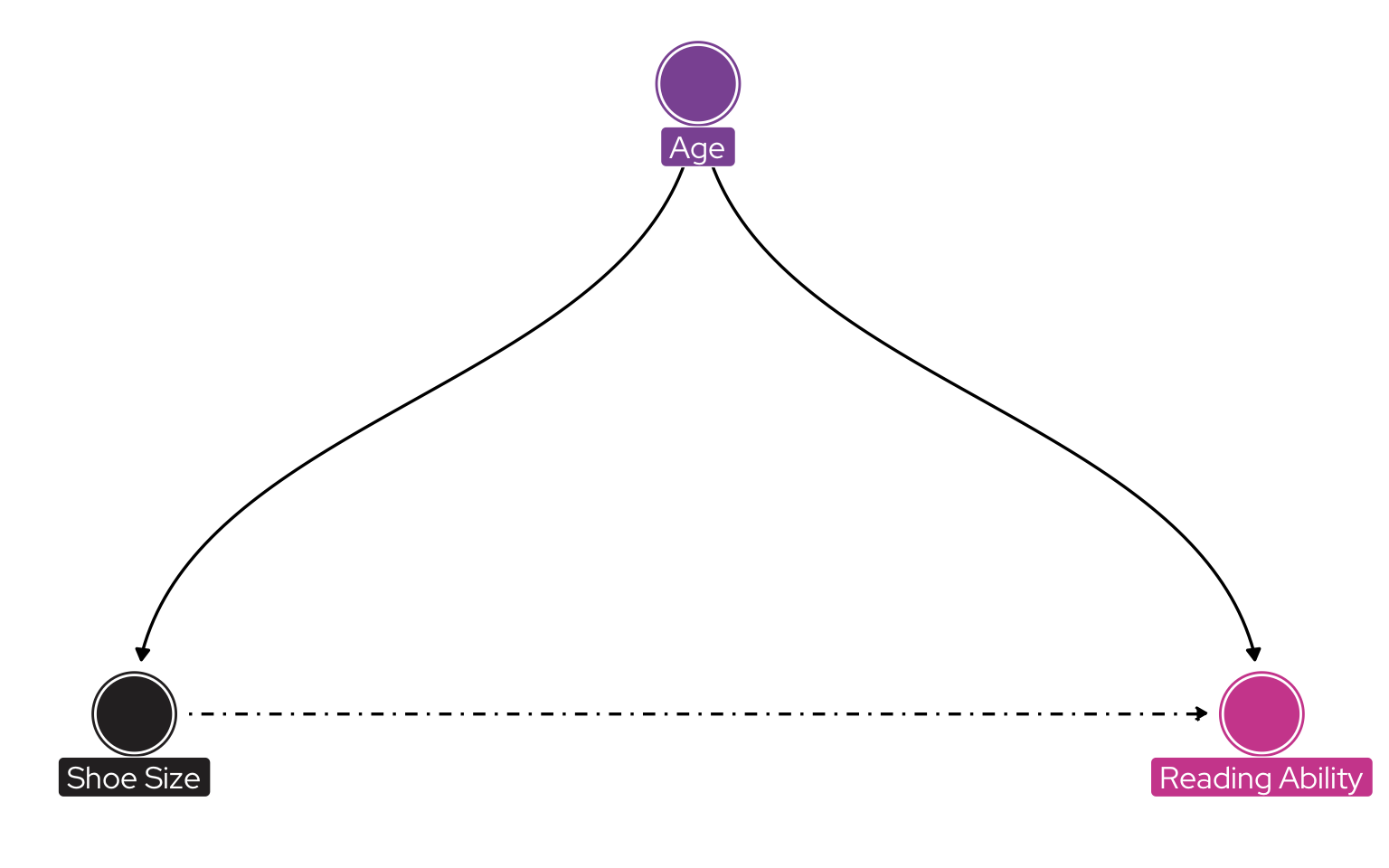

Why might shoe size and reading ability be correlated among children?

Age is the confounder in this instance.

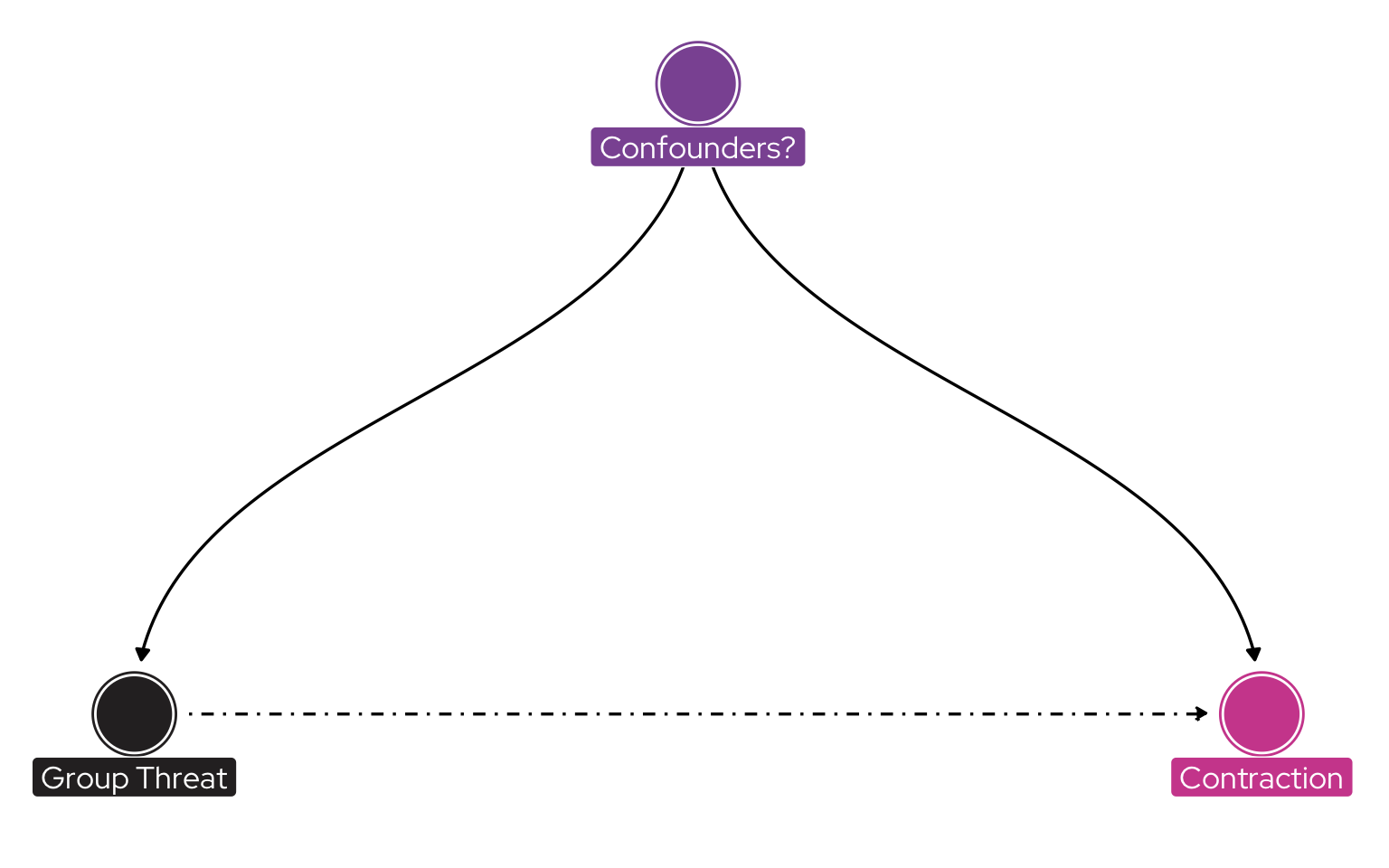

Why might demographic threat and boundary contraction be associated in the general population?

See Abascal (2020)

See Abascal (2020)